The terrace of the Ubud hotel strikes the appropriate tropical tone. Coconut trees border it and a profusion of shade trees reach out to shelter it from the sun. Just beyond the infinite pool a verdant rain forest covers the landscape up the slopes of Gunung Batakau, a conical volcano that anchors the view, interrupted only by profoundly green rice paddies.

The pretty postcard utopia works perfectly from this viewpoint. But danger lurks! Instead of trekking down into the gorge and its cacophony of devilish sounds, I have connected to the internet to book an overnight in the desert.

Images of barren hillsides and empty vistas dance in my head, a temptation that I do not resist. I reserve the last room at the Panamint Springs Resort. With Elisabeth, I will spend New Year’s Eve in stark surroundings and the dry air of Death Valley, as jarring a contrast as can be entertained from the moist equatorial climate of Bali.

The driving force behind the decision to escape to Death Valley for the holiday is not the abundance of festivities but the understanding that I would be free to explore the park without being pestered at every turn. The scenery that envelops my hotel (and that stimulated my interest in this Indonesian island) is not, for all practical purposes, accessible to independent travelers. On the trail into the gorge, it wasn’t long before a local approached me and offered his services as a guide. When I declined, he proceeded to tag behind me a little too close for the purpose of casual social interaction. Minutes later, a toll taker who was seated on the other side of a makeshift barrier halted my progress when I could not pony up the required fee.

Let my people go!

To maximize the time spent in Death Valley, we spent the night before the last night of the year in Ridgecrest, a discouraging community that is neither on a ridge nor near a crest unless the slight bump of Lone Butte qualifies. City forefathers probably eyed the nearby Sierra Nevada range with envy and reasoned that a little marketing sleight of hand wouldn’t hurt anybody. Unless you happened to be an early settler whose visions of alpine meadows collapsed in the middle of barren desert plains.

Ridgecrest is not a base of operations to anything, save the Coso Rock Art district, a notable collection of Indian petroglyphs, which warrants a detour. The National Park Service oversees its archeology but because the site lies on the sprawling Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake, access is limited to U.S. citizens on public tours coordinated by the Maturango Museum. Those denied visitation privileges can contemplate the mystery of a naval installation almost the size of Delaware, but unlike the state, nowhere near any water.

The shortest route to Death Valley passes by Trona, a spectacular example of municipal calamity. Dilapidated homes and abandoned businesses stretch along the base of a low ridge. Row after row of exposed squalor gives the impression the town was evacuated precipitously. Trash collects against chain link fences that delineate plots of gravelly home ownership. Two churches, each with a fresh coat of pain, provide the only sign that life has not fully departed. A backdrop of a lunar landscape after a resounding explosion completes the grim picture. When summer temperatures top 35 degrees with regularity, pollutants from a nearby plant add to the apocalyptic dread.

I could not bring myself to scout the desolated streets to shoot photography. To document social disintegration with a camera hints at exploitation and opportunism. The justification of reporting as a means to educate only minimizes slightly my resistance.

Even in winter scant precipitation falls on the floor of Death Valley. Rainfall totals increase with elevation and the two ranges that ring the park’s namesake valley, the Armagosa and Panamint, capture water and, higher up, snow. By the time we reached the upper reaches of Wildrose Canyon, snow patches hung to the north faces. Farther, the barren slopes hosted pinyon pines and junipers and a decent blanket of snow. Enough of it made progress a little hairy and I ditched the car to continue on foot. Ideally, I would like to head up Telescope Peak but the access road to climb the 3,368-meter summit is closed for the season. Even in summer, it requires a high-clearance four-wheel-drive vehicle.

Ten hefty charcoal kilns mark the trail head to both Telescope Peak and to Wildrose Peak, a neighboring summit 605 meters shorter. Nearly eight meters tall, the kilns produced fuel for two silver lead smelters 40 km away in the late 1870s. When the ore quality in the Argus mines deteriorates, the Modock Consolidated Mining Company closed the kilns after only a year. The owner did well for himself and his son, a teenager at the time, would go on to do exceedingly well and eventually build himself a little house on the ranch his folks had purchased.

I went up a short ways up the Wildrose Peak trail, enough to get a great view of the canyon and the distant Sierra Nevada crest appropriately named. I decided to return to the car by hiking cross country, intoxicated by the thin dry air and fragrant pitch of the trees.

The popular imagery of desert grandeur relies on sweeping sand dunes wrapped in a Lawrence of Arabia moment. Not quite the Sahara, Death Valley boasts nonetheless of two sand dune fields. The tallest ones rise to about 180 meters in the Eureka Valley in a remote corner of the park – and a 45-minute drive from the Palisades glaciers, the southernmost in the U.S. The dunes at Mesquite Flat can be reached by a short stroll off the main park highway. As the sun descended behind the Panamint Mountains, it was a great time to trudge in the dunes interspersed with mesquite trees, keeping an eye out for its thorns.

To reach our upscale digs at the Panamint Springs Resort, we followed the highway over steep Towne Pass. The descent on the other side was precipitous. We pulled in as the sun sank behind the Inyo Mountains. To call it a resort is to stretch the truth to the point of lying. More a motel than a hedonistic temple, I have fond memories of it because I always stop for a beer. When I inquired about a potential New Year’s Eve menu, the reply was that “we offer over 100 beers.”

Under new ownership, the motel’s public rooms feel more threadbare than I remember them. When it is warm – and even two thirds of a kilometer higher than the park headquarters at Furnace Creek, it gets plenty hot – kicking back on the veranda with one or more of those hundred beers is mighty pleasant.

Other than the motel at Stovepipe Wells, the nearest accommodations – or any dwellings - are in Lone Pine, a good 80 km away. This isolation is not good for rates. But on the final day of 2008, the final room at the grand resort could be had for fewer than one hundred dollars.

We met up with a French couple living in New York City who included a stop in the desert as part of an end-of-year tour of California. They shared their hilarious impressions of Buttonwillow, Tehachapi and, you don’t say, Ridgecrest, where they had spent the previous night across the street from us. The pair lived in Hong Kong for six years and traveled extensively in Asia before relocating to Manhattan. The thrill of San Francisco and the Big Sur coast, they found, died down without indecision in these communities, better appreciated from a rear view mirror. With no small irony, the wife pronounced Ridgecrest “surprisingly affordable.” They said they encountered another town, far less appealing if that was a possibility, about 30 minutes our of Ridgecrest…

We toasted New Year’s Eve on Eastern Standard Time with the assistance of una bottiglia di proseco smuggled in for the occasion.

And we toasted the New Year by joining a ranger and a sizeable crowd on a tour of the sand dunes. An hour later I headed toward the tallest one. The trip there is a succession of ups and downs until I got close enough to figure out which ridgeline to follow. A young girl and her mother tried their hand at hurling themselves down a dune atop a large plastic saucer. I ran all the way down, keeping my balance in extremis.

And we toasted the New Year by joining a ranger and a sizeable crowd on a tour of the sand dunes. An hour later I headed toward the tallest one. The trip there is a succession of ups and downs until I got close enough to figure out which ridgeline to follow. A young girl and her mother tried their hand at hurling themselves down a dune atop a large plastic saucer. I ran all the way down, keeping my balance in extremis.

The effect of the Italian champagne lingered and I managed to fool a pair of Italian tourists who was enjoying a picnic outside the Furnace Creek Ranch with my language skills. I love it!

We spent the last part of the day in the pastel assortment of Artists Drive, a one-way dwindling ribbon of a road that slithers amid chocolate, pink, taupe and blond rocks. Because Elisabeth had no time off beyond her regular weekly ration and one-way plane or train fares called for a deeper purse than we possess, I drove all the way back to Santa Barbara to return her home.

We spent the last part of the day in the pastel assortment of Artists Drive, a one-way dwindling ribbon of a road that slithers amid chocolate, pink, taupe and blond rocks. Because Elisabeth had no time off beyond her regular weekly ration and one-way plane or train fares called for a deeper purse than we possess, I drove all the way back to Santa Barbara to return her home.

The next day I was off again.

The next day I was off again.

First destination was the mountains of Big Bear Lake, under a respectable layer of snow compliment of a recent storm. The Hwy 18 off ramp was backed up by cars heading up to Lake Arrowhead, one of several that cradles in the spine of the San Bernardino range. I chose to ignore that red flag until I got myself in a traffic jam a few turns up Hwy 38, the next road up. After recalling an interminable delay much higher on the slopes that took a good hour to resolve itself, I flipped the car around and started up the backdoor entrance to the lake on Hwy 330, the last possible road.

Even at nearly twice the distance, I am confident I got to the Cougar Crest trailhead faster than if I had remained in traffic, inching my way. Dressed up for the season – it is winter after all – I traipsed atop packed snow in search of the Pacific Crest Trail junction that had eluded me on a prior visit. It is but four kilometers, a short distance made somewhat more arduous by the snowpack.

Views of the towns on the lake’s south shore accompanied me all the way, with Snow Summit and Bear Mountain ski areas providing the backdrop. The scenery energized me and tempted me to extend my visit to take in a ski day. The reality is that both are small ski areas that would be packed, doubtless, with holiday hordes.

Views of the towns on the lake’s south shore accompanied me all the way, with Snow Summit and Bear Mountain ski areas providing the backdrop. The scenery energized me and tempted me to extend my visit to take in a ski day. The reality is that both are small ski areas that would be packed, doubtless, with holiday hordes.  Instead I exited this island in the sky for a nighttime drive through the desert to Laughlin, motivated by a record low room price of about $25 at the Tropicana Express. This generosity was extended on the Saturday night of a holiday week-end, no less, when rates typically skyrocket. As is often the case and in counterintuitive fashion, lowest rates pop up not with individual properties but on consolidators’ sites. I booked my room at http://www.hotels.com/. It was fine for the purpose. The clientele of the casino depressed me. My preference is the Harrah’s because it sports a small sandy beach on the Colorado River. Many years ago, management comped me a room and tossed in a generous food and beverage credit. It didn’t take long before I settled in a chaise lounge, my lips closing around the straw from the cocktail glass. The Arizona bank of the river never seemed so close.

Instead I exited this island in the sky for a nighttime drive through the desert to Laughlin, motivated by a record low room price of about $25 at the Tropicana Express. This generosity was extended on the Saturday night of a holiday week-end, no less, when rates typically skyrocket. As is often the case and in counterintuitive fashion, lowest rates pop up not with individual properties but on consolidators’ sites. I booked my room at http://www.hotels.com/. It was fine for the purpose. The clientele of the casino depressed me. My preference is the Harrah’s because it sports a small sandy beach on the Colorado River. Many years ago, management comped me a room and tossed in a generous food and beverage credit. It didn’t take long before I settled in a chaise lounge, my lips closing around the straw from the cocktail glass. The Arizona bank of the river never seemed so close.An In-N-Out Burger (my only entree to the fast food industry) employee recommended the Harrah’s buffet as “the only place where I’ll eat in this town.” I filled up on breakfast goodies before crossing the Colorado River under dull skies.

The car received its sustenance in Bullhead City where a Nevada state patroller who felt no particular duty to pump gas into his cruiser and money into his state’s filling stations joined me at the Maverick pumps. Each gallon transferred into my car’s tank kept 30 cents (8 cents a liter) in my wallet.

The drive to Hoover Dam at Lake Mead is a bit longer on the Arizona side than through Nevada but I opted for it nevertheless. Not many distractions along the way other than a billboard that exhorted me to rent a machine gun, to “try one” at a Las Vegas gun store. Lest our more enlightened brethren shudder at the thought, customers do not take these weapons for practice at the local bank/mall/school/church/office. The fun comes in pulverizing a target within the respectable confines of the store’s range. Rentals come with a minimum of 25 rounds of ammunition, but that must not buy much time with a machine gun. It’s gotta make you feel invincible, manly, American!

A couple of years ago the city of Dorchester, Mass., sponsored a billboard endorsing safe sex practices. According to a news report, it left some residents “shaking their heads” at the sign, which promotes condom use, because it can be seen from a nearby school. Guns=healthy; condoms=pervert.

Traffic goes through a police security checkpoint before getting to Hoover Dam, a formality that is dispensed with a simple wave. A bridge bypass is being built to avoid driving on the dam altogether. The Federal Highway Administration predicts it will be completed by September 2010, an optimistic projection given that only the support towers for the Arizona and Nevada approaches have been completed.

The roadway atop the dam brings motorists eye level with Lake Mead and affords a front-row view to the declining water storage that has dropped 30 meters since the turn of the century. The 160-km long reservoir now holds about 48 percent of its capacity. Unsightly bathtub rings encircle the shoreline. After lowering boardwalks down to the water level some marinas have now closed, their boats floating too far below the decks.

Engineers have designed plans for a new water intake to bring water to parched (and wasteful) Las Vegas to avoid shortages when the lake’s level dips below the existing two pipes. Other schemes look to tap into the water table underneath rural Nevada’s rangeland some 500 km away. It’s been done before. Aqueducts siphon water from the Sierra Nevada, Owens Valley and Colorado River to the Los Angeles region: the farthest source, the California delta, is 715 km away.

Overdrafts from Lake Mead do not only concern profligate Las Vegas users. The reservoir impounds snowmelt water from the Colorado, Virgin and Muddy rivers, in total draining a six-state basin (Nevada, Utah, Arizona, Colorado, Wyoming and New Mexico). Downstream, California and Mexico round out the list of interested parties.

Overdrafts from Lake Mead do not only concern profligate Las Vegas users. The reservoir impounds snowmelt water from the Colorado, Virgin and Muddy rivers, in total draining a six-state basin (Nevada, Utah, Arizona, Colorado, Wyoming and New Mexico). Downstream, California and Mexico round out the list of interested parties. I explored a bit of the Lake Mead backcountry: besides the ubiquitous lake, the park encompasses hundreds of thousands of hectares albeit very few maintained trails. Wind squalls discouraged much exploration but within the sheltered recesses of Redstone the cold of the day was tolerable.

Not much activity at Echo Bay. The marina overlooking the Overton Arm felt deserted and slightly spooky. I zigzagged past the Mormon towns of the Moapa Valley before heading out toward St. George. Instead of the straight shot on I-15, I left the freeway in Littleton on the Arizona Strip and followed the base of the Shivwits Mountains into Utah where Joshua trees kept me company and snow dusted the road near the pass. The sun sunk quickly and bathed the southern Utah sandstone scenery in vivid colors.

Not much activity at Echo Bay. The marina overlooking the Overton Arm felt deserted and slightly spooky. I zigzagged past the Mormon towns of the Moapa Valley before heading out toward St. George. Instead of the straight shot on I-15, I left the freeway in Littleton on the Arizona Strip and followed the base of the Shivwits Mountains into Utah where Joshua trees kept me company and snow dusted the road near the pass. The sun sunk quickly and bathed the southern Utah sandstone scenery in vivid colors.

My hotel for the next two nights showed more signs of affordability: $30 for the first, $25 for the second! Motel 6 forever! St. George is a good base for a return visit to Zion. The six degrees below zero (but bluebird skies) ushered me along. With great anticipation, I climbed the lower reaches of the sublime trail to Angels Landing. Until Refrigerator Canyon the few patches of snow I encountered were mostly to the sides. Once in the shade of the narrow passage the trail was covered in snow and ice. Walter’s Wiggles, too, sported a thick layer of packed snow rendering passage precarious. Quite ready to prove the Visitor Center’s ranger wrong, I set out to climb the steep approach to the final destination. Quickly, very quickly, I was on my knees grabbing on to the cable to avoid a fatal fall hundreds of meters to the canyon floor. Normally at waist level, the cable laid at my feet, nearly buried in snow.

My hotel for the next two nights showed more signs of affordability: $30 for the first, $25 for the second! Motel 6 forever! St. George is a good base for a return visit to Zion. The six degrees below zero (but bluebird skies) ushered me along. With great anticipation, I climbed the lower reaches of the sublime trail to Angels Landing. Until Refrigerator Canyon the few patches of snow I encountered were mostly to the sides. Once in the shade of the narrow passage the trail was covered in snow and ice. Walter’s Wiggles, too, sported a thick layer of packed snow rendering passage precarious. Quite ready to prove the Visitor Center’s ranger wrong, I set out to climb the steep approach to the final destination. Quickly, very quickly, I was on my knees grabbing on to the cable to avoid a fatal fall hundreds of meters to the canyon floor. Normally at waist level, the cable laid at my feet, nearly buried in snow.

Instead of pursuing a climb on all four, I picked another trail into the quiet high country opposite Angels Landing. A great meadow of white expanse and a frozen cataract greeted me. Back at Scout’s Lookout a group of young hikers asked about the path to Angels Landing. I offered a wager that they would not make it…

Instead of pursuing a climb on all four, I picked another trail into the quiet high country opposite Angels Landing. A great meadow of white expanse and a frozen cataract greeted me. Back at Scout’s Lookout a group of young hikers asked about the path to Angels Landing. I offered a wager that they would not make it…

On the other side of the Virgin River bend Zion canyon hides in the shade longer and is much colder. I climbed gingerly up into Echo Canyon but at the Hidden Canyon junction, the trail disappeared under a mound of snow. Even with a careful calibration of my step, progress became hazardous. The sight of the river 300 meters below me did not provoke confidence and I turned around.

On the other side of the Virgin River bend Zion canyon hides in the shade longer and is much colder. I climbed gingerly up into Echo Canyon but at the Hidden Canyon junction, the trail disappeared under a mound of snow. Even with a careful calibration of my step, progress became hazardous. The sight of the river 300 meters below me did not provoke confidence and I turned around.

Minute by minute the shade from the slanted sun engulfed more of Zion Canyon. On the other side of the tunnel the open Checkerboard Mesa basked in dusk glory. Splashes of now covered red and yellow sandstone bluffs and reflected the sun’s last rays. The road, quite a bit higher than in Zion Canyon, sported numerous icy spots but was still eminently navigable. I left the park momentarily to say hello to the herd of buffalo on the grounds of the Zion Mountain Resort. During my last visit with Eric, we were both surprised that the buffalo meat on the menu came from a ranch in another state.

Minute by minute the shade from the slanted sun engulfed more of Zion Canyon. On the other side of the tunnel the open Checkerboard Mesa basked in dusk glory. Splashes of now covered red and yellow sandstone bluffs and reflected the sun’s last rays. The road, quite a bit higher than in Zion Canyon, sported numerous icy spots but was still eminently navigable. I left the park momentarily to say hello to the herd of buffalo on the grounds of the Zion Mountain Resort. During my last visit with Eric, we were both surprised that the buffalo meat on the menu came from a ranch in another state.

The air was delightfully crisp in a way that sharpens appreciation of nature’s scents. The day was ending and I wanted for it to continue, to prolong my suspended state on the deeply etched plateaus of southern Utah.

The air was delightfully crisp in a way that sharpens appreciation of nature’s scents. The day was ending and I wanted for it to continue, to prolong my suspended state on the deeply etched plateaus of southern Utah. The cold front that plowed over the rest of the state and plunged temperatures below -30° in the northern half crept southward the following day. Utah’s southwestern corner is often immune to the fury of such systems. It earned the nickname of Dixie because the climate is indeed much milder in winter. And it most certainly remained warmer than in Salt Lake, Park City, even Cedar City, but the skies turned an ugly grey and the wind kicked in, turning a brief pause at the Virgin River Canyon Recreation Area even briefer.

The cold front that plowed over the rest of the state and plunged temperatures below -30° in the northern half crept southward the following day. Utah’s southwestern corner is often immune to the fury of such systems. It earned the nickname of Dixie because the climate is indeed much milder in winter. And it most certainly remained warmer than in Salt Lake, Park City, even Cedar City, but the skies turned an ugly grey and the wind kicked in, turning a brief pause at the Virgin River Canyon Recreation Area even briefer.

After finding success in snapping a picture of the Arizona state line sign as I drove past it at 120 kph, I repeated the feat a few kilometers later where I-15 crosses into Nevada. It is not that easy to focus on a subject while also keeping the steering wheel in reasonable alignment with the freeway.

After finding success in snapping a picture of the Arizona state line sign as I drove past it at 120 kph, I repeated the feat a few kilometers later where I-15 crosses into Nevada. It is not that easy to focus on a subject while also keeping the steering wheel in reasonable alignment with the freeway. The sight of the power plant near Moapa belching smoke into the air signaled the approach to Las Vegas. The thick haze draping the bowl in which it sits confirmed it. Not a pretty sight.

The sight of the power plant near Moapa belching smoke into the air signaled the approach to Las Vegas. The thick haze draping the bowl in which it sits confirmed it. Not a pretty sight.

A calamitous financial wind has blown on the city since my last visit in April. Celebrated as the epicenter of American money-making dynamism, the region has been slapped hard by the collapse of the mortgage/real estate/banking/investing/lending speculative illusion. Phenomenal growth gives way to the highest rate of foreclosed properties in the nation. Economic prowess may have been the result of accounting wizardry but the evictions are real. On the Strip, ground zero for the excess of the last decade, half-finished high rises rub shoulders with exclusive resorts not too happy to share close real estate quarters with skeletons. Prescient, the House of cards withers.

A calamitous financial wind has blown on the city since my last visit in April. Celebrated as the epicenter of American money-making dynamism, the region has been slapped hard by the collapse of the mortgage/real estate/banking/investing/lending speculative illusion. Phenomenal growth gives way to the highest rate of foreclosed properties in the nation. Economic prowess may have been the result of accounting wizardry but the evictions are real. On the Strip, ground zero for the excess of the last decade, half-finished high rises rub shoulders with exclusive resorts not too happy to share close real estate quarters with skeletons. Prescient, the House of cards withers.Still on an Asian high, I booked a table at Sushi Roku, hidden in the midst of the Forum Shops at Caesars Palace next door, a neighboring destination that took me a good half hour to reach on foot. Not a gambler, I could have lost my shirt had I been tempted by the discreet sales at the profusion of luxury boutiques that lined my path. Gianni Versace, Salvatore Ferragamo, Gucci, Fendi, Louis Vuitton, Yves Saint Laurent, Tiffany, Bvlgari, Bottega Veneta, Hermès, Giorgio Armani, Dior, Chanel and others competed to put a new watch on my wrist, a ring on my finger, a wallet in my pocket and a new shirt, too, on my back.

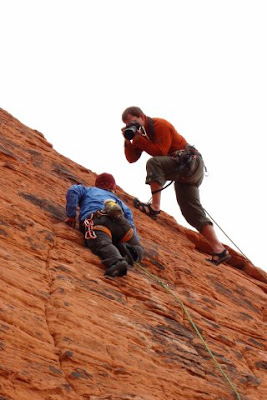

Thirty minutes from the Strip nothing has changed for a few millennia at Red Rock Canyon. The current economic anxiety recedes to a distant distraction. I played hide-and-seek among towering boulders and rock faces, prying my way through narrow passages that threatened to keep me wedged for good. I made my way to a pitch high in the Calico Hills where rock climbers were practicing and photographed the photographers. True to expectations I found ice in Ice Box Canyon on the other, shaded side of the Scenic Loop.

Thirty minutes from the Strip nothing has changed for a few millennia at Red Rock Canyon. The current economic anxiety recedes to a distant distraction. I played hide-and-seek among towering boulders and rock faces, prying my way through narrow passages that threatened to keep me wedged for good. I made my way to a pitch high in the Calico Hills where rock climbers were practicing and photographed the photographers. True to expectations I found ice in Ice Box Canyon on the other, shaded side of the Scenic Loop.

From the seclusion of my Bellagio digs I watched a half dozen cycles of the choreographed fountain ballet dance against the backdrop of the Tour Eiffel and the Arc de Triomphe. Paris in the desert. The reality made unreal. I wanted to lose myself in the gorgeous pool but the air temperature was a single degree when I dropped by and the water could not have been all that much warmer.

From the seclusion of my Bellagio digs I watched a half dozen cycles of the choreographed fountain ballet dance against the backdrop of the Tour Eiffel and the Arc de Triomphe. Paris in the desert. The reality made unreal. I wanted to lose myself in the gorgeous pool but the air temperature was a single degree when I dropped by and the water could not have been all that much warmer.

No comments:

Post a Comment